Suppose Robert E. Lee had laid hands on a shipment of AK-47s in 1864. How would American history have unfolded? Differently than it did, one imagines.

Historians frown on alt-history, and oftentimes for good reason. Change too many variables, and you veer speedily into fiction. The chain connecting cause to effect gets too diffuse to trace, and history loses all power to instruct. Change a major variable, especially in a fanciful way—for instance, positing that machine-gun-toting Confederates took the field against Ulysses S. Grant’s army at the Battle of the Wilderness—and the same fate befalls you. Good storytelling may teach little.

What if Japan had never attacked Pearl Harbor? Now that’s a question we can take on without running afoul of historical scruples. As long as we refrain from inserting nuclear-powered aircraft carriers sporting Tomcat fighters into our deliberations, at any rate.

When studying strategy, we commonly undertake a self-disciplined form of alt-history. Indeed, our courses in Newport and kindred educational institutes revolve around it. That’s how we learn from historical figures and events. Military sage Carl von Clausewitz recommends—nay, demands—that students of strategy take this approach. Rigor, not whimsy, is the standard that guides ventures in Clausewitzian “critical analysis.” Strategists critique the course of action a commander followed while proposing alternatives that may have better advanced operational and strategic goals.

Debating strategy and operations in hindsight is how we form the habit of thinking critically about present-day enterprises. Critical analysis, maintains Clausewitz, is “not just an evaluation of the means actually employed, but of all possible means—which first have to be formulated, that is, invented. One can, after all, not condemn a method without being able to suggest a better alternative.” The Prussian sage, then, scorns Monday-morning quarterbacking.

That demands intellectual self-discipline. “If the critic wishes to distribute praise or blame,” concludes Clausewitz, “he must certainly try to put himself exactly in the position of the commander; in other words, he must assemble everything the commander knew and all the motives that affected his decision, and ignore all that he could not or did not know, especially the outcome.” Critics know how a course of action worked out in retrospect. They must restrict themselves to what a commander actually knew in order to project some realistic alternative.

It doesn’t take too much imagination to postulate alternative strategies for Imperial Japan. Indeed, eminent Japanese have themselves postulated alternatives. My favorite: the high naval command should have stuck to its pre-1941 playbook. The Pearl Harbor carrier raid was a latecomer to Japanese naval strategy, and it was the handiwork of one man, Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto. Had Yamamoto declined to press the case for a Hawaiian strike, or had the high command rebuffed his entreaties, the Imperial Japanese Navy would have executed its longstanding strategy of “interceptive operations.”

In other words, it would have evicted U.S. forces from the Philippine Islands, seized Pacific islands and built airfields there, and employed air and submarine attacks to cut the U.S. Pacific Fleet down to size on its westward voyage to the Philippines’ relief. Interceptive operations would have culminated in a fleet battle somewhere in the Western Pacific. Japan would have stood a better chance of success had it done so. Its navy still would have struck American territory to open the war, but it would have done so in far less provocative fashion. In all likelihood, the American reaction would have proved more muted—and more manageable for Japan.

The Hollywood version of Yamamoto puts the result of Pearl Harbor well, prophesying in Tora! Tora! Tora! that “we have awakened a sleeping giant and filled him with a terrible resolve.” That’s a rich—and rather Clausewitzian—way of putting it. Clausewitz defines a combatant’s strength as a product of capability and willpower. Yamamoto alludes to the United States’ vast industrial and natural resources, depicting America as a giant in waiting. He also foretells that the strike on Battleship Row will enrage that giant—goading him into mobilizing those resources in bulk to smite Japan.

Assaulting the Philippines may have awakened the sleeping giant—but it’s doubtful it would have left him in such a merciless mood. He would have been groggy. Here’s Clausewitz again: the “value of the political object” governs the “magnitude” and “duration” of the effort a belligerent mounts to obtain that political object. How much a belligerent wants its political goals, that is, dictates how many resources—lives, national treasure, military hardware—it invests in an endeavor, and how long it sustains the investment.

It pays a heavy price for goals it covets dearly. Lesser goals warrant lesser expenditures.

The Philippine Islands constituted a lesser goal. The archipelago constituted American territory, having been annexed in the aftermath of the Spanish-American War of 1898. But the islands also lay on the far side of the Pacific Ocean, thousands of miles from American shores. And they had been absent from daily headlines since the days when imperialists like Theodore Roosevelt wrangled publicly with anti-imperialists like Mark Twain about the wisdom of annexation. Americans reportedly had to consult their atlases on December 7 to find out where Pearl Harbor was located. The Philippines barely registered in the popular consciousness—full stop.

Regaining the Philippines, then, would have represented a political object commanding mediocre value at best—especially when full-blown war raged in Europe and adjoining waters, beckoning to an America that had been Eurocentric since its founding. Chances are that the U.S. effort in the Pacific would have remained wholly defensive. The U.S. leadership would have concentrated resources and martial energy in the Atlantic theater—keeping its prewar promise to allied leaders in deed as well as in spirit.

Bypassing the Hawaiian Islands, in short, would have spared Japan a world of hurt—as Admiral Yamamoto foresaw. Forbearance would have granted Tokyo time to consolidate its gains in the Western Pacific, and perhaps empowered Japan’s navy and army to hold those gains against the tepid, belated U.S. counteroffensive that was likely to come.

Now, let’s give Yamamoto his due as a maritime strategist. His strategy was neither reckless nor stupid. Japanese mariners were avid readers of the works of Alfred Thayer Mahan, and going after the enemy fleet represents sound Mahanian doctrine. Crush the enemy fleet and you win “command of the sea.” Win maritime command and contested real estate dangles on the vine for you to pluck afterward.

Image: Creative Commons.

And indeed, the Mahanian approach did pay off for the Imperial Japanese Navy—for a time. Japanese warriors ran wild for six months after Pearl Harbor, scooping up conquest after conquest. But a vengeful giant can regenerate strength given adequate time. As Yamamoto himself predicted, Japan could entertain “no expectation of success” if the war dragged on longer than six months or a year.

Doing less—or forswearing an effort entirely—always constitutes a viable strategic option. Doing nothing was an option Japan should have exercised rather than assail Pearl Harbor. That’s the lesson from alt-history.

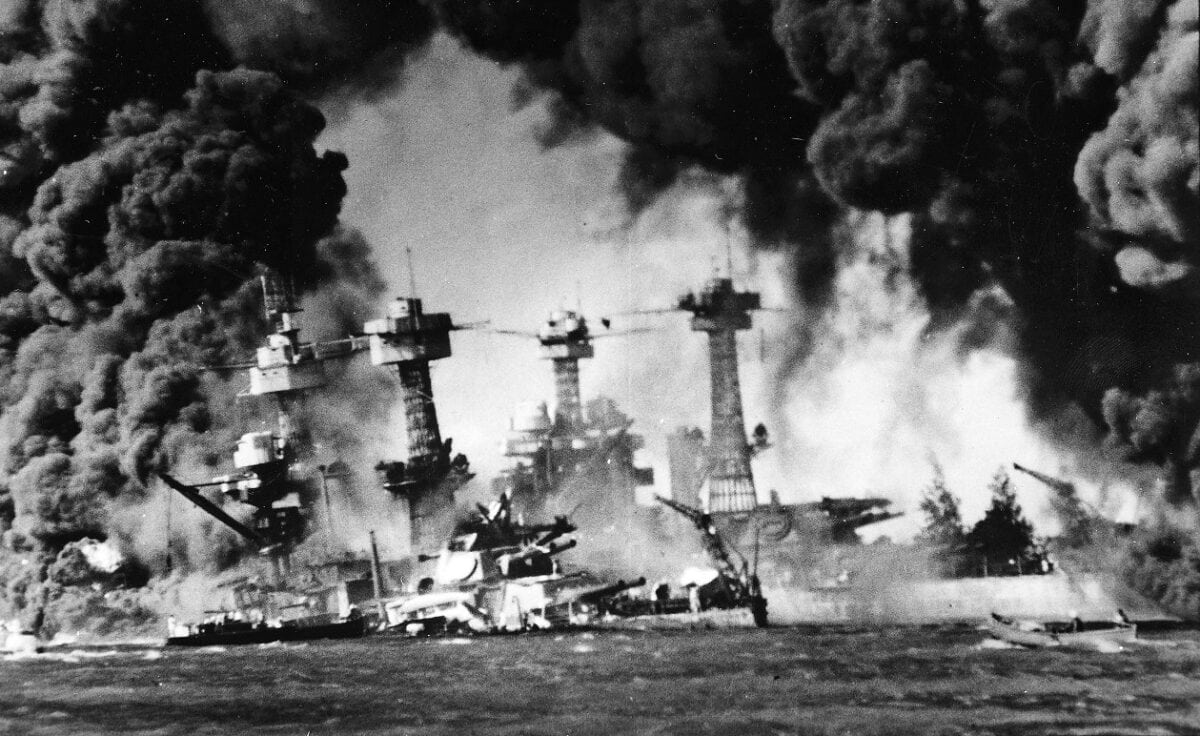

Battleship USS West Virginia sunk and burning at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. In background is the battleship USS Tennessee.

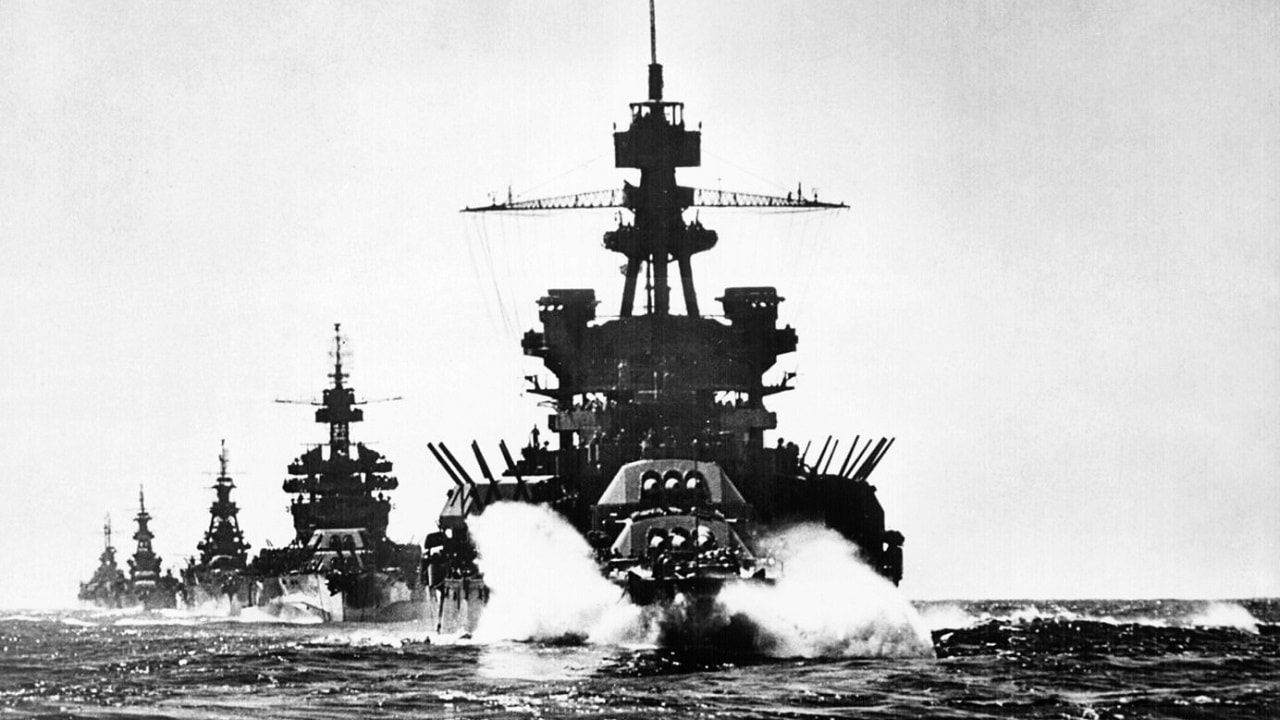

Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941. USS California (BB 44) after the attack. Official U.S. Navy photograph, now in the collections of the National Archives. (9/9/2015).

Pearl Harbor 2. Image Credit: Creative Commons.

MORE: World War III – Where Could It Start?

MORE: A U.S.-China War Over Taiwan Would Be Bloody

James Holmes is the inaugural holder of the J. C. Wylie Chair of Maritime Strategy at the U.S. Naval War College.

David Chang

May 1, 2023 at 5:43 pm

God bless people in the world.

Thanks to Dr. Holmes for discussing this serious question.

Because of this question, I first think of the modern version of Japan naval strategy that Vice Admiral Satō Tetsutarō published the naval strategy paper “On the History of Imperial National Defense” published in 1910.

In this atheism paper, Vice Admiral Sato thinks about the wrongness of Japan’s defense policy, and discusses the scope and nature of the military that Japan people should maintain and strengthen as the research of military history. For Japan, enhancing military strength is the first and foremost to enhance its own national strength, and by extension, it has the significance of safeguarding the nation-state. This is because Japan must win the competition for survival in order to survive, and Japan is also under the law of victory and defeat. Vice Admiral attaches great importance to the fate of Japan as a nation, especially mentioning the immortality of the nation, that is, the existence of the emperor. In order to preserve Japan’s independence and continue to progress, military force must be used to bring Japan’s enemies to their knees. He thinks that the duties of national defense are to maintain the security and welfare of the nation, to protect and extend commerce, and to prevent the entry of enemy troops into the nation in times of distress. As this principle, Japan must never invade other countries or resort to weapons to promote their own national interests, but to avoid the vigilance of other countries, defend the state power, and maintain peace. So he declares that the purpose of arming should be to ensure the country’s financial resources, promote economic prosperity, and thus ensure the great cause of thousands of generations.

Vice Admiral Sato considers the size of military power is related to economic power and population, and believes that it is wrong to devote all national power to the military power necessary for the country’s survival. The country cannot be demeaned because of the economic damage caused by the expansion of military power for the sake of national defense. As for the casualties of war, there is a risk of losing adult males who will be the labor of families and industries. Also, due to the nature of the fighting, casualties tend to be greater in land battles mobilizing reserves than in naval battles. Regarding the geographical environment closely related to the level of military power, the author believes that in order to counter Russia, South Korea should be regarded as a buffer zone, with the advantage of naval power instead of land power for national defense, and he suggests that Japan should concentrate its power on the sea. He also criticize people who advocate deploying troops to the Korea peninsula and northeast China for misunderstanding the principles of the offensive. Therefore, Vice Admiral Sato believes that the strategy of expanding the country and offensive strategy advocated by the defense policy of the Japan Empire in 1907 is contrary to the original intention of armaments.

Just like Chess, early mistakes will lead to future failures. Even if people do the best to save the disadvantage, it is difficult to avoid failure and can only try to make a draw.

God bless America.

FSW3

May 1, 2023 at 8:31 pm

Here’s a thought, what if Japan had struck north into Siberia, like the army wanted?

They could have coordinated with Germany. This would have forced the USSR into a two front war. It would also have opened up a large amount of natural resources for Japan.

The Navy could have struck into the Dutch East Indies. Again obtaining resources from a weakened enemy.

In both cases they would have avoided directly confronting the US. At the time, the US had a very strong pacifist movement. It would have hindered the US response. It was only Pearl Harbor that caused the collapse of the America First movement.

Just a thought.

David Chang

May 2, 2023 at 10:29 am

God bless people in the world.

Although Japan’s national defense policy at the end of the 19th century prescribes that Japan will lose in the war of the 20th century. However, the strategy of General Yamamoto is still an important question, because the Japan Socialism Army pushes the Japan Confucianism Navy to follow the policies determined by the Army. Therefore, General Yamamoto’s task is to protect the Kingdom of Japan.

Because General Yamamoto knows the future of the Kingdom of Japan, Bushido is the political thought of Japan Navy in World War II. Die for the king.

The interception strategy of the Japan Navy originated from the Tsushima Strait War in 1905. In this war, the Japan Navy confirms the doctrines of attrition strategy with maneuver tactics. But General Yamamoto’s problem is that they don’t have enough ships and soldiers to implement the interception strategy in the Western Pacific. The maneuver tactics are difficult to achieve the strategy goals of the Japan Navy in the Western Pacific battlefield. First, the Japan Navy does not agree with the Japan Army’s invasion, so the navy only cooperates with the army for the transportation and supply of Japan’s military in mainland China.

However, the people in Japan who believe socialism and evolution think that the United States is the enemy after World War 1, so the Japan navy will fight the U.S. navy. So General Yamamoto’s strategy question is where is the decisive war area to the big U.S. Navy. By the finances and industries of the Japan Kingdom, the Japan Navy doesn’t have sufficient ships, supply, and repairing factories to complete the interception strategy to guard the shipping line from Japan to Indonesia. Therefore, General Yamamoto decides to fight the U.S. Navy first, by which could save supplies and earn the bedtime

So the Japan Navy fought the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor, and some U.S. Navy generals respect General Yamamoto.

As the contrary of this military theory, the CCP makes the U.S. Navy to take the invitation of PLAN for fighting in a designated area expected by atheism political parties of one-China.

Moreover, if there was no Pearl Harbor naval battle, when the Japan socialism army occupied all China and built more naval factories, the Japan Navy would be the so-called the Second Island Chain defender. The U.S. Navy will have a decisive battle in the Okinawa-Guan. However, if the Japan Army established the Southeast Asia Socialism Alliance, it would make the US-Soviet Socialism Alliance more close and make German and Hitler’s Socialism government to occupy Iran more easy.

Finally, each of us will bear the moral responsibility for this.

God bless America.

David Chang

May 2, 2023 at 10:33 am

God bless people in the world.

Although Japan’s national defense policy at the end of the 19th century “presages” that Japan will lose in the war of the 20th century. However, the strategy of General Yamamoto is still an important question, because the Japan Socialism Army pushes the Japan Confucianism Navy to follow the policies determined by the Army. Therefore, General Yamamoto’s task is to protect the Kingdom of Japan.

Because General Yamamoto knows the future of the Kingdom of Japan, Bushido is the political thought of Japan Navy in World War II. Die for the king.

The interception strategy of the Japan Navy originated from the Tsushima Strait War in 1905. In this war, the Japan Navy confirms the doctrines of attrition strategy with maneuver tactics. But General Yamamoto’s problem is that they don’t have enough ships and soldiers to implement the interception strategy in the Western Pacific. The maneuver tactics are difficult to achieve the strategy goals of the Japan Navy in the Western Pacific battlefield. First, the Japan Navy does not agree with the Japan Army’s invasion, so the navy only cooperates with the army for the transportation and supply of Japan’s military in mainland China.

However, the people in Japan who believe socialism and evolution think that the United States is the enemy after World War 1, so the Japan navy will fight the U.S. navy. So General Yamamoto’s strategy question is where is the decisive war area to the big U.S. Navy. By the finances and industries of the Japan Kingdom, the Japan Navy doesn’t have sufficient ships, supply, and repairing factories to complete the interception strategy to guard the shipping line from Japan to Indonesia. Therefore, General Yamamoto decides to fight the U.S. Navy first, by which could save supplies and earn the bedtime

So the Japan Navy fought the U.S. Navy at Pearl Harbor, and some U.S. Navy generals respect General Yamamoto.

As the contrary of this military theory, the CCP makes the U.S. Navy to take the invitation of PLAN for fighting in a designated area expected by atheism political parties of one-China.

Moreover, if there was no Pearl Harbor naval battle, when the Japan socialism army occupied all China and built more naval factories, the Japan Navy would be the so-called the Second Island Chain defender. The U.S. Navy will have a decisive battle in the Okinawa-Guan. However, if the Japan Army established the Southeast Asia Socialism Alliance, it would make the US-Soviet Socialism Alliance more close and make German and Hitler’s Socialism government to occupy Iran more easy.

Finally, each of us will bear the moral responsibility for this.

God bless America.